Read Chapter 1 here There came days when Mother walked the floor, wringing her hands, while our father tried reasoning with her, and reassuring her. It was no use. Our young uncle was away working and no word had come from him for months. He was rumored to be hauling dynamite for construction work at…

Category: Prairie Childhood

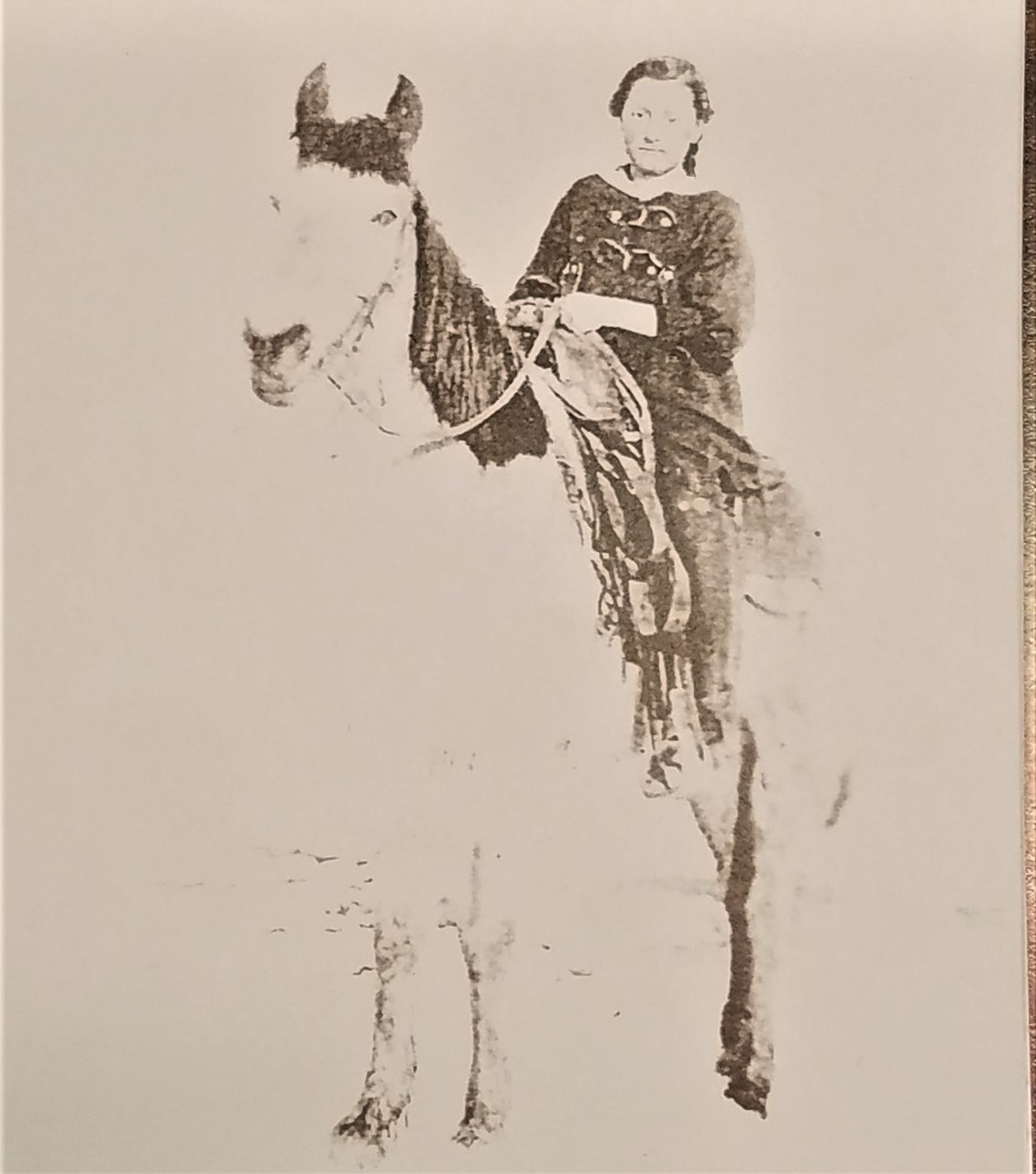

Prairie Childhood, A Memoir By Anna M. Nickol – Chapter One

Editors note: We hope you enjoy this story by Anna M. Nickol (1909-2005) about her family’s homestead in Toole County, MT. E-City Beat will publish the story a chapter at a time as they become available from Anna’s nephew Greg Nickol as he transcribes from the original book publication. Prairie Childhood, a Memoir by Anna M. Nickol…